Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

This article was originally published in theMay 7, 2012, issueofNew Yorkmagazine.

She will be remembered fondly by so many as a generous teacher, editor, and mentor.

And its fair to say her legacy is wholly secure.

Toni Morrison never liked that old seventies slogan Black is beautiful.

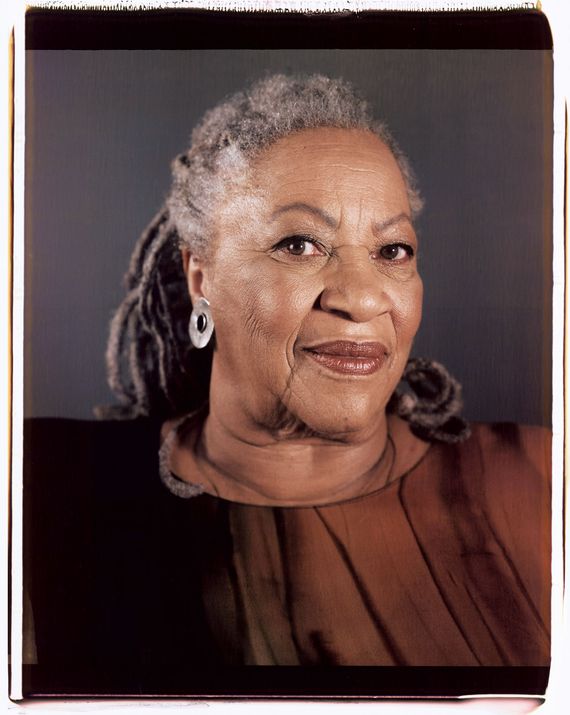

Morrisons voice is as layered and visceral as her writing.

The author growls, purrs, giggles, and barks.

Discussing politics, her voice rises in indignation before cresting and breaking into a loud chuckle.

(They should have that in the military, or the prisons a little affirmative action!

Lets bring some white guys in!)

She surrenders to a wheezing, shoulder-shaking, freight-train laugh when describing a particularly gruesome Funny or Die video.

She booms theatrically in recounting the ghost stories her parents would tell every night.

(Sharpen my knife, sharpen my knife, gonna cut my wifeshead off!)

Itll be with me like a shroud, or a cape, forever.

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Wofford, and still thinks of that as her real name.

It sounds like some teenager what is that?

She wheeze-laughs, theatrically sucks her teeth.

Thats a Greek name.

People who call me Chloe are the people who know me best, she says.

Chloe writes the books.

Toni Morrison does the tours, the interviews, the legacy and all of that.

I still cant get to the Toni Morrison place yet.

That might be because Chloe knows Toni doesnt belong to her.

Which isnt to say that she didnt break seemingly impenetrable barriers.

No one benefited more from her bold stance on the barricades of inclusiveness than Morrison herself.

And then the tide receded.

Countervailing forces swept in.

Political correctness became a wedge issue, cultural studies a joke.

But two decades after she won her Nobel, Toni Morrisons place in the pantheon is hardly assured.

That she belongs as much with Faulkner and Joyce and Roth as she does with that illustrious sisterhood.

Not that there wasnt integration of a sort.

Lorain, and occasionally the Wofford house, was mixed by necessity.

We were mostly poor-ish, and we had no choice except help one another, Morrison explains.

Nor was it quite the sepia-toned portrait of class solidarity that Morrison occasionally paints.

Morrison has often spoken of vacillating between her mothers quiet optimism and her fathers unvarnished hatred of white people.

In school, though, everyone had to mix.

But she was way ahead of the rest of us.

The whites voted for her for class treasurer!

She was also in the drama club and the National Honor Society.

She was so liked, and she was focused.

They didnt have affirmative action then.

She was respected because she was an achiever.

The only way she could fit in was by standing out.

After school, Chloe kept close to home.

She and her three siblings would dance to her grandfathers violin or the songs of her mother, Ramah.

She had the most beautiful singing voice in the world, and she could sing anything, Morrison says.

People used to come from all around to hear her in church, and go weeping.

This was all language, she says now.

If they said green, you had to figure out in your head what shade that was.

And you only heard voices.

So everything else you had to build, imagine.

In those days, she says, people didnt move this close to the water.

Now its like the most expensive property in the village.

A few months after she won the Nobel Prize, the boathouse burned down to the Earth.

But theres something a little too new about it.

Though Slade was an abstract painter, none of this work is his; its been put into storage.

One closet hides an elevator, which Morrison presciently installed not long before her hip replacement in 2010.

I have gotten up to fourteen minutes of walking, she says.

I go outside, around the decks.

She also owns a couple buildings upriver.

And just a few weeks ago, she rented a new Manhattan apartment.

Shes attributed her house-gluttony to all those childhood evictions.

Its an archetypal postwar homecoming story, reminiscent ofThe Odyssey.

Morrisons fifties were very different from those of her haunted hero.

She had opted for college at historically black Howard University, expecting some sort of Utopia for African-American intellectuals.

That Morrisons firsthand political awareness came relatively late might, paradoxically, explain its importance in her work.

But it does to me.

So I look at it.

Yet its only now that Morrison is reexamining that decade for the first time.

Emmett Till was killed in 1955.

It was all lying there, like seed corn the seeds that blossomed in the sixties.

Homewas only half-done when Slade died, around Christmas 2010.

Morrison says it was pancreatic cancer and recklessness.

He was one of those Chinese medicinetype crazy people.

- He also collaborated with his famous mother on clever childrens books likePeeny Butter FudgeandWhos Got Game?

The Ant or the Grasshopper?But [he was] very careless, she says.

When they get grown, you cant smack em.

After Slades death, Morrison putHomeaway for months.

Its the closest shes ever come to writers block.

But she would never use the term herself.

Im getting a little better, Morrison says now.

Its spring, and my forsythias are out.

Her next book is a special comfort at the moment, but writing has always been a solace.

The only thing I do for me is writing.

Thats really the real free place where I dont have to answer.

To people who dont know her, she might appear to be a diva, he says.

But in the work and personal relationship, there is nothing of that.

Morrison considers humility a handicap.

It works against you, she says.

She is fond of testing journalists who ask either too little or too much.

Youre writing a little piece, arent you?

No, in fact; she was told its a feature.

Oh, this is too much.

Can I approve it?

Thats not really done, I say.

Can I edit it?

I tell her Ill be nice.

Youre gonna tell all these funny stories!

Then she tells a few more stories.

She has an incredibly adorable side, says Claudia Brodksy, a Princeton colleague and a close friend.

Which I shouldnt be talking about, because shes not gonna show it.

Shes told me: For the public, I have to be very severejust keep it at bay.

Otherwise they just devour you.

It was during the fifties that Chloe became Toni Morrison.

She was discouraged from writing on her first chosen topic: the black characters in Shakespeare.

In 1964, pregnant with Slade, Morrison split from her husband.

She hasnt said much publicly about the marriage, except that Harold wanted a more subservient wife.

He didnt need me making judgments about him, she once said, which I did.

Soon she took a job in Syracuse, editing textbooks for a division of Random House.

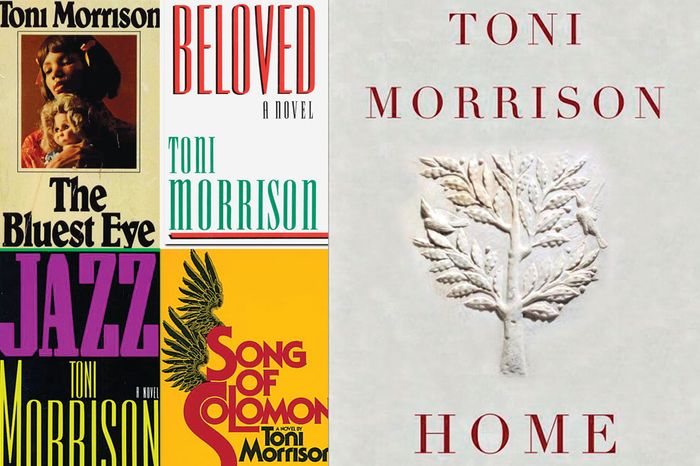

The Bluest Eyewas published in 1970.

The former complained about her negative portrayals while the latter dismissed her for trying too hard.

Required reading, Morrison once said about it.

Therein lies the success.

The political and academic tide was lifting her boat in writing and also in publishing.

He would end up editing all but one of her subsequent novels.

Bernstein also made Morrison a trade editor at Random House effectively his black editor.

Morrison the editor had an agenda, as she freely admits.

I thought that I was contributing powerfully to the so-called record.

The problem was that the institutions that were elevating her books were still ghettoizing them.

A Random House salesman told her he couldnt sell her books on both sides of the street.

Two objects dominate this island.

One is a bowl of stones the size of bread loaves.

So I got three.

They looked like they were all calling to me.

Did she ship them in from Thailand?

Oh God, no!

I hadnt seen it in years, she says.

Mounted on clear plastic, it lies open like a diploma case.

I think they were trying to be cute, she says, chuckling.

With reporters and hangers-on mobbing her office, she had her assistant call her friend Claudia Brodsky.

Now, the assistant commanded.

Brodsky pushed her way past the throng and was hustled into Morrisons office.

She closed the door, Brodsky recalls, and she just started dancing.

It was coy, silent, and joyous.

Ill never forget it in my life.

The result, Song of Solomon, vaulted Morrison into the arms of a broader public.

John Leonard declared it a privilege to review.

It is closer in spirit and style toOne Hundred Years of SolitudeandThe Woman Warrior.

It builds, out of history and language and myth, to music.

It won the 1977 National Book Critics Circle Award.

Gottlieb soon persuaded Morrison to quit her editing job.

Its oblique and nonlinear, but also an allegory of Americas shame and a shiver-inducing ghost story.

And it came along at an auspicious time.

(Its a stupefying work, says Brodsky.

It gives you nightmares.

)Belovedwas on the best-seller list for 25 weeks and earned a permanent place on school reading lists.

Its hurtful, Morrison says now.

Morrison saw it differently, of course.

Because all that is clouded by the box youre put in as a Black Writer.

Im actually gonna think for a minute, she says.

No ones asked me that question.

After another minute, she brings up Mr. Jeremy Lin.

Then its, Were gonna hold back his injuries so we can sell more tickets.

You know what I mean?

Brodskys apologiais for both Morrisons success and its aftermath.

Even as her sales and status have held strong, Morrisons books have ceased to qualify as news.

But critically, at least, she did succumb.

NeitherParadisenor her next novel,Love, met the bar raised byBelovedandJazz(never mind the Nobel Prize).

Both Philip RothsAmerican Pastoraland Don DeLillosUnderworldcame out in 1997, the yearParadisedid.

But theyre very different writers, very, very different from me.

Well, one self-edits and one doesnt.

Morrison and Walker do share a link: Oprah Winfrey.

She also began touting a succession of self-help mentors.

Morrison was arguably the first author Winfrey devoted her starmaking power to and probably the most ambivalent.

She told friends she didnt wantBelovedto be a film, and she prayed Oprah wouldnt play the lead.

Oprah did, and it was a notorious bomb, which Morrison didnt like.

(Now she denies ever being apprehensive about the movie.)

Morrisons ambivalence spilled over recently when Oprah broached the death of Morrisons son.

But she bristled when Oprah suggested the show would help her get closure on Slades death.

Dont ever say that word, Morrison said.

Theres never closure with the death of a child.

She says now that she was happy to discuss her son, but not in detail.

Theres no language for that especially not the language of closure.

Oprah is a generous woman, she says, but I did want to say the guarantee of happiness?

What is that about?

Certainly nothing that Faulkner or Woolf had anything to do with.

In colleges, she worries about being a slave to intellectual fashion.

She remembers visiting the University of Michigan a few years ago and perusing its course catalogues.

My books were taught in classes in law, feminist studies, black studies.

Every place but the English department.

Brodsky believes Morrisons insecure place in academe is symptomatic of a deeper cultural problem.

Theyre like, How dare she not be this mammy?

That [role] works if theres one book and its life-affirming in this very obvious way.

I think its because you cant quite mammy-ify her entirely that theres a great resentment.

The next novel looks like another zigzag.

All the men I know are intellectuals, including Slade, but Ive never written about them.

Another character is deeply into fashion, which is why Morrison is currently fascinated with Lady Gaga.

Shes done it, Morrison says approvingly.

Fashion with a capitalF.

After our talk, Morrison walks me to the back window, which overlooks a pier on the river.

Its brand-new; the old pilings blew away in a storm last year.

Its stronger now than my house, she says.

I thought,Oh great, itll fade in the weather, and it wont look so cartoonish.

But the man who built the dock told her it wasnt outdoor wood; they had to lacquer it.

So the bench, with its childlike TMs scrawled over the back, might well outlast its famous occupant.

Morrison parries questions about posterity, about what becomes of Toni Morrison after Chloe Wofford passes on.

I do think about what they call my papers, she says.

She told her older son, Ford: Put them someplace where no one can write some stupid biography.

Last year she canceled a contract for a memoir: I am not interesting to me.

Theres no discovery there.

Shed rather preserve a sense of mystery the source of fiction, after all.

And if the biographers insist on knowing, she says, I think Id prefer they got it wrong.